Zhuangzi once said: “If you tell the monkeys they will get three chestnuts in the morning and four in the evening, they will be angry. But if you say four in the morning and three in the evening, they will be happy.” People often laugh at this as “monkeys being tricked,” but what exactly did the old man do? Was it really “tricking,” or was it a form of adjustment? In the end, didn’t the monkeys still get seven chestnuts a day? The monkeys were angry, and then they were pleased. But no one blamed the old man for his “deception.” Why is that?

This can be compared to our system of holiday adjustments. Take the Qingming Festival as an example: according to national law, one day off is granted. Based on established practice, one day is given, and to create a longer holiday, the authorities “adjust” by combining the weekend days before or after with that one day, making it into a three-day “long weekend.” On the calendar, these days are not additional breaks, but rather human-made shifts. The essence is to move weekends around, turning scattered rest days into a continuous holiday. Of course, this means the borrowed weekend days must be repaid later by working extra days. Some people compare this to Zhuangzi’s “chestnuts,” jokingly calling it “three in the morning and four in the evening.”

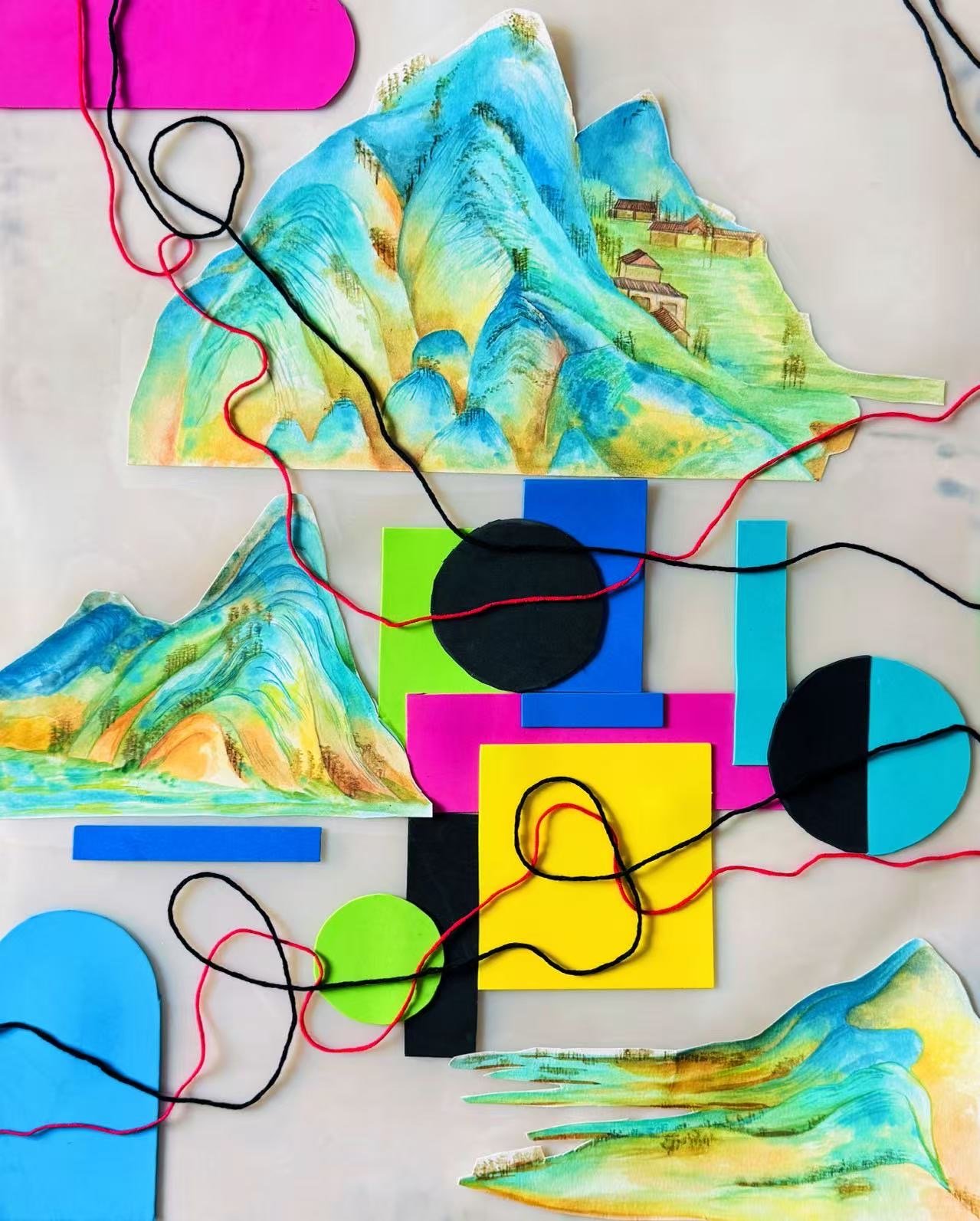

So what about us, the “angry monkeys”? In truth, whether the holiday is three days or not, the change is only in appearance. One type of “adjustment” is splitting days apart, another type is merging them together. To put it plainly: it’s still the same number of rest days. Let’s look at our little “chestnut story”:

A company arranges staggered shifts: one day on, two days off. Some employees like it, thinking the rest days are longer. Others hate it, saying the continuous working days feel exhausting. For example, if you work four days in a row and then rest for three, some people enjoy the extended break, but others complain about the fatigue of the long work stretch. If the manager rearranges it, alternating one day off every two workdays, the outcome is still the same total number of days, but opinions differ. Some say, “This is perfect, I get to rest often.” Others complain: “Why not just give me three days off together?”

In the end, whether it’s joy or anger, it’s all about one’s own perspective and position. If it brings benefit, people are happy; if it doesn’t, they are upset. So it all comes down to self-interest. The adjustment itself—whether “separating” or “combining”—is only a redistribution of days off. It does not increase or decrease the total.

From an economic perspective, combining holidays (“merging”) is better for boosting consumption and stimulating the economy, while separating them (“splitting”) is better for maintaining steady work schedules. That’s why authorities often favor the merging model: more people travel, spend money, and benefit industries. From an individual perspective, however, opinions vary: some prefer extended breaks for traveling, others like shorter but more frequent rests.

Back to Zhuangzi’s story: the old man did nothing wrong, and neither did the monkeys. It wasn’t really deception—just adjustment. Whether it’s three chestnuts in the morning or four, the total is the same. Similarly, whether we split or merge holidays, the total number of days off doesn’t change. People may complain or resist out of habit, but in the end, it’s still the same. Why not just accept it and be happy?